From the ascent of Isabel Perón* to the position of President of Argentina in July of 1974, through the military junta that deposed her in March of 1976, until the autumn of 1983, which saw the collapse of the junta in the wake of their devastating loss in the Falklands War, the political left of Argentina was subjected to a relentless wave of state-sponsored political terror that murdered anywhere from 10,000-30,000 people and tortured and imprisoned tens of thousands more.

The actual number can’t be verified because most of the junta’s violence was conducted in secret, with the military, security forces, and the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance (of military and police death squads) “disappearing” small bands of guerrillas, but also trade unionists, writers, journalists, artists— anyone who was determined to speak out against the junta, be it ideologically, economically, or politically. This decade is known as the “Dirty War”, but let’s use quotation marks because it was, in fact, no war at all; it was the asymmetrical application of political murder by the powerful against those who dared to stand against their campaign of terror.

Truly:

In 1983, the National Commission on Disappeared People (received testimony that) described how “prisoners were drugged, loaded onto military planes, and thrown, naked and semi-conscious, into the Atlantic Ocean.” A vast majority of those who were killed disappeared without a trace and no record of their fate.**

Notably, the campaign also targeted students, beginning with the infamous “Night of The Pencils, a series of kidnappings and forced disappearances, followed by the torture, rape, and murder of 10 high-school students that began on the evening of September 16, 1976.” One of the survivors later gave testimony:

“…they gave me electric shocks in my mouth, my gums, and my genitals. They tore out one of my toenails. It was very usual to spend several days without food.”

This period of state brutality and murder***, conducted in secret within a hidden network of state-run prisons and torture facilities, provides the historical backdrop for Our Share Of Night, Mariana Enriquez’s masterpiece of a novel set in Argentina before, during, and after the junta’s campaign of unaccountable, unrestrained violence.

And while the actual details of the “Dirty War” are not the story that propels this book, this decade of political terror is its subject; it is everywhere within it, a dark, swirling, omnipresence— an inescapable madness— that gives the novel a profound, unshakeable human resonance. Our Share Of Night transcends political, historical, and horror fiction by uniting them. It is an unforgettable novel, a roadmap for how fiction can help us understand and remember the past by making it tangible, physical, and emotionally alive on the page. It is also absolutely terrifying.

+++

Others will summarize the brilliant, gripping plot of Our Share Of Night better than I, but in brief: the story centers around two children raised within an elite, dark, and powerful demonic cult that traces its roots back to colonial England**** and has blossomed among the upper classes of 20th century Argentina. Rosario is the daughter of the cult’s leaders, a family that controls vast natural resources and has used its dark power to amass a huge fortune. Juan is a boy from an impoverished family who requires urgent treatment for a potentially fatal heart condition. When Rosario’s uncle, a heart surgeon, operates on Juan, he discovers that the boy is able to embody The Darkness, the powerful demonic force that the cult believes can ultimately offer a form of immortality to those who are devoted to its secrets. Those who can manifest The Darkness are incredibly rare and are known by the cult as “mediums”— precious vehicles for the cult to communicate with and learn from The Darkness. After Juan survives his heart surgery, Rosario’s family “buys” him from his parents and brings him to their sprawling estate in order to conduct manifestations and rituals with him.

Over the years (and its horrors), Juan and Rosario become close, end up marrying, and have a son named Gaspar. But as The Darkness and its followers continue to take a tremendous physical and psychological toll on Juan, he dedicates himself to preventing Gaspar from becoming a medium as well. Juan continues to serve the cult while keeping Gaspar’s potential power as a medium hidden, until ominous and terrifying tragedies begin to befall Gaspar, his friends and his family, and a final confrontation becomes inevitable.

While this summary hardly does this brilliant novel justice, the devil is literally in the juxtaposition of Enriquez’s grotesque details and the impact they have on her very human characters. The cult of The Darkness is horrific in its brutality, and Enriquez pulls no punches in describing their crimes which, for me, were unimaginable until I read them on the page— kidnapping, torture, disfigurement, dismemberment, starvation, imprisonment, disease, much of it done for sadistic pleasure, inflicted upon the poor and marginalized, and almost all of it done under the delusion of expanding personal power within the cult and society at large.*****

But in parallel with all of the physical brutality, surrounding it, Enriquez has imagined a rich, complex supernatural system, filled with powerful spells and symbols, where interior spaces transform from their quotidian appearances into shifting, terrifying, haunted nightmares. Enriquez shows us just enough of the arcana without dwelling on its mechanics— we see it and feel it through the characters, and we experience the real-world emotional consequences of the cult’s power without knowing precisely how it all works. And it is that unknown “how?” that is at the root of the book’s true horror, as uncertainty and the unknown (and unknowable) drive the narrative further toward the void.

This feeling is overpowering because Our Share Of Night privileges the position of the reader and understands how literary horror should function; it lets us in on just enough of its secrets, it shows us some of what is hidden from its characters, and this knowledge, like Hitchcock showing us a ticking bomb, creates an almost unbearable atmosphere of dread when, in the novel’s final section, that perspective is removed, and everything we know is possible, all of it terrible, seems to be lurking in the next sentence we’re about to read.

In that sense, Our Share Of Night functions explicitly as a series of nightmares. I don’t mean that as a metaphor, I mean it literally; in the book’s supernatural moments, which lurk behind every locked door, Enriquez’s writing feels like “dream logic” where time slows down, becomes inescapable, presses down on the characters, where landscapes transform, where horrors arise and disappear, rife with meaning, but unable to be fully understood, relentlessly and without respite. While reading, I found myself unable to talk about this book, not because of its complexity, but for fear I would diminish its meaning by describing it in my own “waking” language when, instead, it had activated my imagination in a way that felt like I was dreaming. As a reader, I found myself returning to sentences in order to distinguish what was on the page versus what was happening in my own imagination, which had been activated to new levels of paranoia and fear.

And as we experience these pages as a lucid nightmare, carried forward by this deeply resonant power throughout the book, it is also clear that, in the world of Our Share Of Night, The Darkness and its power are real. It is not a magical delusion, the book doesn’t play games with its world building, it is all real; the literal disfigurement of society and its people, forever marked by the lust for a secret and violent power. This the atmosphere of the novel, tying its historical reality to its timeless, otherworldly violence. Here, on these pages, the nightmare is made both literal and dreamlike.

Argentina’s horrors and those of the cult converge, echo, and rhyme; the Darkness consuming limbs and people, hidden prisons and torture chambers, anonymous buildings that hide terrible secrets behind their anonymous doors, and the unconscionably brutal collusion among the powerful to “disappear” people, to murder them, without consequence or justice or a full possibility of understanding which, in the end, brings us to an absence, the ultimate horror of Our Share Of Night. People vanish and die, become palpable absences, and for what purpose? The vanity of the elite, the eternal continuation of their injustice, the cycle of exploitation, all of it without any real meaning. And there, in this realization, we come to understand the “why” of this brutality clearly— it is done because it can be done. In the end, none of it can be undone, it can only end in a perpetual void, allowing the past to linger on, to hang, suspended and airless, irreconcilable.

+++

Notes:

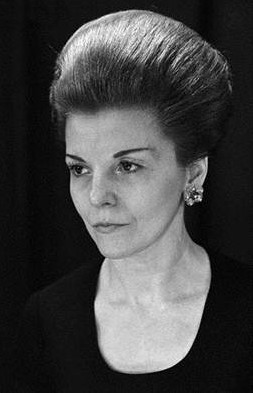

* I had never seen a photo of Isabel Perón until after I read this novel and was reading up on the junta and the so-called “Dirty War”, and it turns out she is the EXACT image in my mind’s eye of the character of Mercedes in this book. I mean, EXACT. Which I am sure will now haunt me forever. Crazy!!!

** Friends, the continued availability of “helicopter ride” T-shirts should be a wake up call to everyone in this country as to the actual intentions of the contemporary right wing. These are not benign memes, but like so many right wing “jokes”, an explicit, direct threat that is based on the terrible history of state murder. And yet.

*** It should of course be said that this campaign of terror was part of a region-wide program of so-called “anti-communist military government” called Operation Condor, which included Pinochet’s Chile and which was covertly (but enthusiastically) supported by the United States government. And so, to read this book as an American is to understand the role our nation played in facilitating and supporting these horrors– nourishing them with resources, publicly ignoring them, never accounting for them, and actively working to keep them secret.

**** The colonial origins of the Cult of The Darkness in the novel are fascinating and tie into the history of political power within Argentina, the socio-economic privilege of European immigrants in Argentina, and the 19th century English cult The Hermetic Order of The Golden Dawn, but are also a perfect framework for a historical examination of the brutal exploitation of people and resources by the elite classes, all of which is too much for this review to address meaningfully, but upon which this book does a brilliant job of building historical context for the cult’s dark power.

***** It also bears mentioning that this is a deeply Gen X novel, one that points a clawed finger squarely at the selfish brutality of older generations who cling to what they have inherited, revel in cruelty, and who are obsessed with defeating mortality and perpetuating their hold on social power at any cost (but especially at the cost of others). The arrogance and resentments at the heart of the cult are not just historical, but symptoms of our contemporary reality, driven by greed and the exploitation of the young by the old; there are moments that call to mind Pasolini’s anti-fascist film SÁLO, aligned with that film’s deep understanding of the dynamics of inter-generational brutality.